Daniel L. Kelley

The greatest challenge facing the intellectual mind of the 21st century lies not in the discovery of new ideas, but in the rejection of our ancestors� myths. The truths so ardently sought after by endless philosophers have been merely lying in waiting, concealed from humanity�s view behind superstitions and folklore. For philosophy, it has never been the case of attempting to gain an unattainable truth. The past has shown time and time again that the search for undeniable proofs has proven most successful while placed in the care of the most patient of men.

As I will illustrate, much wiser men than myself have grappled with the proofs which plague theology and have consistently failed in their attempts. Due to the prevailing uncertainty of an existent deity and the contradictory characteristics of the Judeo-Christian God, the practice of worshipping such a deity has served as the reinforcement of falsely accepted knowledge. Even worse, the acceptance of these assumptions further serve to stagnant personal growth especially within, but not limited to, within the realms of ethics and rationality.

Only through the acceptance of the most stringently proven truths may we push aside the myths� of our forefathers in our pursuit of unadulterated knowledge. If humanity is ever to reach an era where it is possible to answer some of man�s most resiliently stubborn questions of origin and morality, then we must start from the basest of foundations. Philosophy should not be treated as a study based upon assumptions or linguistic tricks. Rather, it should reflect the minute steps taken ever so cautiously by past philosophers in the hopes of eventually reaching these as of yet unattained truths.

In the same way, one may look upon the life of a person as a type of growth in knowledge. Inevitably, we consciously or unconsciously search for the meaning of our own lives. One psychologist, Abraham Maslow, recognized this individual quest and realized the importance of meeting our basic human needs along the journey. In 1954, he wrote of these needs in his ground-breaking work titled, Motivation and Personality.

Through Abraham Maslow�s proposed classification of human needs, we see an example of the necessities needed for an individual to reach a level of �self-actualization.� It must now be noted that the acceptance of Maslow�s Hierarchy of Needs pyramid is intended to serve only as a rudimentary model of the qualities needed to attain personal autonomy. The intricacies of Maslow�s argument are still within psychological debate, but the essence of his work remains practical enough for our use.

Maslow proposed a classification of human needs into five categories: physiological, safety and security, belongingness and love, esteem, and self-actualization. These needs formed a hierarchy, in which the earlier needs, when not satisfied, supersede the later needs in the hierarchy. Maslow hypothesized that psychological health was possible only when these needs were satisfied. The more these basic needs were not satisfied, the more psychologically disturbed the individual would be. (Lester, Sullivan, Hvezda, and Plourde)

The goal of personal autonomy should be recognized as the most basic underlying pursuit of each individual, not only for its egoistic intentions, but also for the overall good demonstrated by its utilitarian benefits. In short, a person striving for autonomy will reach the eventual conclusion that an altruistic lifestyle may not reap the material rewards as another, but the feelings of self-respect garnished by altruistic behavior vastly outweigh those feelings of pride from material wealth. With this in mind, the terms autonomy and self-actualization will be used synonymously throughout this work.

Yet it is important to remember that the practice of worship, especially within a communal setting, is not without benefits. In some circumstances, these cases may even be considered necessary for the person�s well-being. After all, such practice may very well help an individual reach some of the lower levels of Maslow�s hierarchy; including the third level of Belongingness and Love and the fourth level of Esteem. Although these benefits will become plainly evident, it is necessary to remember the words of a well-known agnostic philosopher. In the now famous BBC debate with F.C. Copleston, Bertrand Russell proclaimed, �The fact that a belief has a good moral effect upon a man is no evidence whatsoever in favour of its truth.� (Hick, 236)

As a demonstration of the application of knowledge (false or not) towards the growth of personal autonomy, we will elaborate on the benefits attained with the worship of a deity even though its existence cannot be proven. By seeing the relationship between the benefits of supposed knowledge among Maslow�s lower levels, we will further be able to recognize the benefits of adhering to the strictest of scientific proofs within Maslow�s level of Self-Actualization.

Of the numerous benefits of worship, one of the most recognizable is the sense of comfort an individual achieves from the practice of religion. The comfort granted with the practice of religion stems not from the familiar, but with the unfamiliar. Religion offers human beings comfort from the unknown. Of course, the greatest unknown of our own imminent death has been masked (to their obvious benefit) by religions across the world.

Noted philosopher, Bertrand Russell addresses religion�s relation to fear in his book Why I Am Not A Christian, by stating:

Religion is based, I think, primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown and partly, as I have said, the wish to feel that you have a kind of elder brother who will stand by you in all your troubles and disputes. Fear is the basis of the whole thing�fear of the mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death. (22)

In a somewhat vain effort to combat this fear, we strive to discover that which has been hidden from our sight. From the fields of science to the humanities, human beings have shown an extraordinary skill in self-deception. Even upon discovering that which has been hidden from us, we continue with the dissection and categorization of the unknown item until it finally becomes beaten and twisted into an object which is understandable to us.

Soren Kierkegaard addresses this concept in the published work Philosophical Fragments:

But what is this unknown something with which the Reason collides when inspired by its paradoxical passion, with the result of unsettling even man�s knowledge of himself? It is the Unknown. It is not a human being insofar as we know what man is; nor is it any other known thing. So let us call this unknown something: God. It is nothing more than a name we assign to it. (Hick, 167)

With the labeling of this unknown object, it finally relinquishes the anxiety and fear of being �unknown.� The same methodological approach has been used since the time of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians in the construction of Gods and demi-Gods. The mythical figures have differed greatly over the centuries, yet the overall message has been the same: Obey God�s law (which normally coincides with dominant moral beliefs of the time) and you shall receive life after death.

The Epicureans were the first philosophers to theorize that the Gods may have been created out of human fear (primus in orbe deos fecit timor). Even though the origins of the comfort gained through the worship of a deity may be disputed, the end result cannot be. There is a common acknowledgement among those who practice religion of a sense of real comfort as a result. The comfort may or may not be an emotion based upon false pretenses, but the benefits remain the same.

More so, organized religion has historically provided a founding point for the enforcement of common morality. While religion has been proven to be as susceptible for corruption as any other powerful organization, any method of enforcing standards set for the overall good of the community is at least intended to be beneficial to the individual. A communal adherence to the standards agreed upon with religion�s intervention likely established one of the earliest forms of Hobbes� social contract, with the exception of a God in the place of a sovereign.

In some cases, the laws ordained within the Old Testament yield even more practical benefits than that of a common morality. Among the Jewish faith, there are a number of dietary laws within the text of Genesis and Numbers which carry the sole function of maintaining a healthy living style. These laws include the refusal to eat meat that has not been thoroughly cooked and adherence to strict guidelines for the consumption of milk and eggs. (Bible, Gen. and Num.)

I am certain that the examples above only represent a small portion of the benefits one may gain with the worship of an unproved deity. In the goal of attaining personal autonomy, the benefits reaped from religion may prove to be essential in achieving the end of self-actualization. The dietary laws exemplified within the Old Testament may help meet Maslow�s first level of needs of the Physiological. Likewise, one may find the sense of comfort gained through a religion�s promise of immortality to be of enormous help in reaching Maslow�s second level of Safety and Security. The obedience towards a common morality seen in many religions may also help an individual reach Maslow�s third level of Belongingness and Love, perhaps even the fourth level of Esteem.

Yet all of the benefits one could gain from the practice of religion can be equally exemplified within the confines of science. Although science has not provided the answers to all of humanity�s questions, it is merely a matter of patience before its discoveries provide the necessary clues to unravel these questions. Most importantly for those pursuing autonomy, science provides an objective view hindered only by time.

Since the Enlightenment Era, science has become the signature of the rationalist. The benefits of adhering to empirical knowledge over the presumptions of faith are twofold. First, science provides a base for attaining autonomy without resorting to the intellectual retardation of religious dogmas. Secondly, the field of science has provided a much more reliable method of gaining the characteristics seen in Maslow�s level of Self-Actualization. For these two primary reasons, science must become the signature of those seeking Maslow�s fifth level of Self-Actualization. Through science, we find the use of the �known� instead of the �unknown.�

As Bertrand Russell eloquently writes:

Science can help us to get over this craven fear in which mankind has lived for so many generations. Science can teach us�no longer to look around for imaginary supports, no longer to invent allies in the sky, but rather to look to our own efforts here below to make this world a fit place to live in, instead of the sort of place that the churches in all these centuries have made it. (Why I Am Not a Christian, 22)

Again, I must stress that the Maslow�s Hierarchy of Needs is only a rudimentary model used to demonstrate the needs of an autonomous being. Yet Maslow identifies nineteen characteristics of the self-actualized being which coincide quite harmoniously with our conception of a self-governed individual. For the sake of simplicity, we shall adopt these characteristics. Key among these characteristics include: clarity of perception, problem-centered, solitude seeking, humbled and respectful, ethical, resistance to enculturation, and sense of humor. (Maslow)

The benefits of worship, however varied they may be, will eventually need to be laid aside in the individual�s pursuit of self-actualization. One can never hope to reach Abraham Maslow�s fifth level of Hierarchy of Needs if held within the limits of believing in an unproved object; whether that object is a deity or not is inconsequential. A self-actualized person cannot rely upon assumptions; they must remain pursuant of truths and reliant only upon the basest of proofs. The limits one places upon themselves while adhering to the belief structure of an organized religion shall forever stagnant their personal growth.

Personal growth is at the heart of searching for the answers to the questions earlier prescribed in the text. Only through the eyes of an autonomous being can we reach the objectivity needed to unveil the answers to our origin, our morality, our purposefulness, etc... Autonomy does not come easy. We will have to make many sacrifices in our traditions and culture, but the rewards shall be greater than anything achieved in the lower four levels of Maslow�s Hierarchy of Needs.

Yet we must still inquire, how does the simple act of Faith limit our ability to govern ourselves?

And most importantly, what are the grounds for agnosticism which is being deemed necessary for self-actualization?

The latter of these two inquiries may become the most difficult circumstance to accept in our goal of becoming autonomous. Generally speaking, the human species has relied on claims of deities transcending the empirical world since recorded history. These separate and distinct �Faiths� all hold a single characteristic in common; none of them are able to provide proof in the form of clear empirical data for the existence of the projected deity.

When an individual becomes aware of its potential to reach beyond the bonds of the physiological, of the search for safety, of finding a sense of belonging, even of surpassing the need for personal esteem, then they face the most difficult challenge of their lives. This challenge resides in the stoic acceptance of themselves and of their reality as experienced by empirical thought.

An autonomous individual does not necessarily have all of the answers to their lives or environment; enlightenment must not lie in the presumed solutions but in the acceptance of the world�s unknowns. They must intrinsically be patient. Fore as discussed earlier, the answers to humanity�s epic questions cannot be found with simple determination. An autonomous being must be able to recognize �unknowns,� and not fall into the trap of assumption.

The strive to find unknowns cannot and should not be halted in the name of autonomy. To do so would be negligent of our human nature. Humans are innately curious of this world. Rightly so, the search for understanding may ultimately be in vain, but the search itself is the only venue which raises us above an instinctual existence.

The philosophical search for understanding can only begin with the strong footing of objectivity. An objectivity which disavows nothing, yet accepts only the meanest of proofs. Through this method we see the impossible relation which faith holds in contrast to the self-actualized person. Faith cannot stand upon the footing of objectivity. For all of its benefits, its existence is marred by assumptions. For the autonomous being, these assumptions would only serve to cloak the reality of themselves and their environment from true sight.

Some of the greatest thinkers have debated the existence of a deity much to their avail. Their inability to produce clear and distinct proof of an existent deity is not grounds alone to reject the possibility of God�s existence, but it is valid grounds to remain skeptical. Fore in the future, a discovery may be revealed that irrevocably concludes the existence of a deity. Until that time, however, the rational man must seek objectivity in thought and deed with the rejection of worship to attain a higher understanding of the world around him.

Before we examine the problems of an existent deity, I must admit my own limitations. Unfortunately, my lack of knowledge of this world�s various religions has led me to concentrate solely upon the Judeo-Christian concept of God. One should not misinterpret this limitation as an acceptance of the practice of worship by other religions regardless of how remote they may be. The overall method of objectivity can and should be applied universally to all religions, regardless of the culture.

In the traditional Judeo-Christian concept of God, the deity has the three main characteristics of being an omnipotent, omniscient, and omni-benevolent being. The first problem we will examine shall draw on this definition of God as being contradictory to what has been perceived by us in the empirical world. This problem has become commonly referred to as the Problem of Evil.

The dilemma is as such:

If God is omnipotent, God can prevent all evil; if God is perfectly good, God must want to prevent all evil; but evil exists; therefore God is either not omnipotent or not perfectly good. Either of these alternatives would amount to the collapse of traditional Hebrew-Christian monotheism. (Hick, 516)

Saint Augustine was one of the initial philosophers who confronted the problem of evil, and consequently his rebuttal has been widely accepted. Essentially, Augustine gave two solutions to the Problem of Evil. The first claimed that evil was merely a privation of good. The second, the aesthetic theme, claimed that �evil exists within it (the world) like the black patches in a painting that contribute in their own way to the beauty of the whole.� (Hick)

While Augustine�s attempt is notable, it ultimately fails. Like his peers, he attacked the problem with the dissecting tools of categorization and left it merely as a more orderly version of the initial problem. According to Augustine�s interpretation, God has inflicted evil upon our world to make us appreciate the overall good of the world. At best, we can conclude from this interpretation of the Problem of Evil that God is omnipotent and partially benevolent, but not omni-benevolent.

Besides disavowing God�s omni-benevolence, the characteristic of omnipotence comes into question when considering the validity of worship. The problem of an all-powerful God in relation to religious worship lies in the uselessness of its practice. An all-powerful master has no purpose for servants. To presuppose a God that requires the aid of its creations assumes that the God is dependent upon something other than itself. In short, such a God is not a necessary being.

John Stuart Mill masterfully addresses this problem in the work, Three Essays On Religion, by stating:

The religious idea admits of one elevated feeling, which is not open to those who believe in the omnipotence of the good principle in the universe, the feeling of helping God�of requiting the good He has given by a voluntary cooperation which He, not being omnipotent, really needs, and by which a somewhat nearer approach may be made to the fulfillment of His purposes. (Castell, Borchert, and Zucker, 176)

Mill reconciles the problem of aiding God with the construction of a deity limited in his powers, but I believe we must go further. While Mill admits there is a problem with serving a supreme being, his work also illustrates the contradiction we find after examining the Judeo-Christian concept of God within our empirical world. The black holes of assumption have consistently falsely supported our notions of a divine being no matter how many linguistic riddles we impose.

Now we must address the problem of our own origin. Even though it is clear that our conception of a Judeo-Christian God contradicts with our empirical experience, is it not impossible that our origin was sparked by a Creator nonetheless?

First, we should distinguish between a deistic view of creation versus the commonly held Judeo-Christian monotheistic view. Deism reached its pinnacle in the 18th century, when deists conceived of a supreme being which sent the universe in motion and promptly stepped away from his creation. In contrast, monotheists maintain belief in a supreme being who seeks a total and unqualified response from his creatures.

In relation to the validity of religious worship, we must completely disavow the purpose of worship in the case of the deist. Worship of an idle deity can serve absolutely no viable end. The only conceivable benefit could be the praise of the deity for creating us, but as the God will not have any positive or negative reaction such a practice is illogical to say the least.

In order for some practical benefits to be assumed, we need to be led into the monotheistic belief system. For the purpose of our inquiry, it is a fair assessment to place the Judeo-Christian conception of God within the religious structure seen in monotheism. As we examined earlier, there are numerous contradictions of reason within the characteristics of the Judeo-Christian God, but in relation to our origin we will soon discover several more.

For the sake of argument, let us allow ourselves to be taken in by the Genesis story of creation. Despite the harm we will endure in our quest to become autonomous, we will turn a blind eye to all the empirical data rejecting the Judeo-Christian belief in creationism. Unfortunately our comfortable position will soon be compromised, as we will discover that even with the religious blinders firmly in place there is no reasonable explanation for the religious practice of worship.

As the traditional authority of the Cosmological Argument, we will use Thomas Aquinas as the staple for an argument of Natural Theology. In short, Thomistic thought centered upon arriving at proofs of God�s existence through facts about the natural world. It is important to note that Anselm�s Ontological Argument is also riddled with innumerable logical discrepancies, but as it is an argument not based upon any empirical support its fallacies fall outside of the realm of our argument.

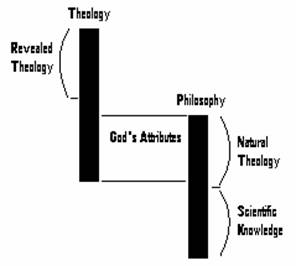

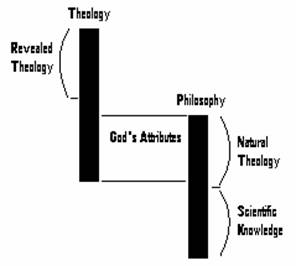

Thomas� propositional view of faith and revelation falls between two distinct categories. The first of which is Theology, or knowledge granted to men by God. The second category is Philosophy, wherein men discern facts to the existence of God. For Thomas, the importance of these categories is within the overlapping of theology and philosophy. For only in this slim margin can man realize the attributes of God.

If Thomas� theory were to be placed within a simplified diagram, it would hence be represented:

While Thomas� belief of God�s attributes can be rationalized through the use of Natural Theology, his support for Revealed Theology lies primarily upon assumptions based upon evidence outside of empirical perception. As a logical being attempting to reach Maslow�s fifth level of Self-Actualization, this assumption is of the utmost concern.

Even with the assumption that the five proofs offered in Thomas� Natural Theology are accurate (which many philosophers have strongly disputed), we cannot by Thomas�s own understanding assume the existence of Revealed Theology. Though the religious blinders remain emplaced, we cannot logically deduce some of the primary practices of worship granted to us by Revealed Theology. These include but are not limited to; the Incarnation of the Trinity, Original sin, the Sacraments, and even creation in time. Thomas� argument attempted to prove the existence of a monotheistic God, yet for those seeking self-actualization his propositional view of faith and revelation point us steadily in the direction of deism., that is an absentee God. Consequently, we have already discerned that a deistic view of creation holds no logical grounds for the practice of religious worship.

Yet, let�s leave the blinders on for a bit longer as we examine our origin utilizing Thomas� theology. If we allow the assumption of God as our creator in the Judeo-Christian sense and even if we overlook the contradictory characteristics of God in this belief structure, we still face tremendous hurtles in reconciling our religious practices with our striving for personal autonomy.

As our God is assumedly proven to be omnipotent, omni-benevolent, and omniscient, we can rest assured that our comfort in the face of the unknown is justified. We can even justify universal morality and natural evil through a variety of seemingly valid arguments within our understanding of God. Yet, we cannot within the realm of reason justify our practice of religious worship.

The reasoning remains simple. Outside of the assertions made by religious institutions, we can have no direct evidence that our perfect God wishes us to practice religious worship. In fact, it is entirely plausible that a God proven to be all-powerful, all-good, and all-knowing would have intended for his creations to eventually break away from religious worship, assuming that the God ever intended for its practice in the first place.

With these logical disputes overwhelming the Judeo-Christian belief in humanity�s origin, what is the path laid open to those seeking to reach Self-Actualization?

As the autonomous being adheres to only the most meanest of proofs, we must place the Creationist view of our origin within the confines of countless other hypotheses offered by scientists and theologians throughout the world. On all points of support, Judeo-Christian belief in Creationism lies within the same pool of doubtable unknowns as Darwinism and Friedrich Nietzsche�s Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence. While the Creationist Argument does not offer valid support for the continued practice of religious worship, we should not hastily accept or reject this argument or any other until indisputable evidence is presented. For the autonomous being, agnosticism remains the only legitimate response.

The famous empiricist, David Hume, illustrates this conception by stating:

All religious systems are subject to insuperable difficulties. Each disputant triumphs in his turn, exposing the absurdities, barbarities, and pernicious tenets of his antagonist. But all of them prepare a complete triumph for the skeptic who tells them no system ought ever to be embraced with regard to such questions. A total suspense of judgment is here our only reasonable course. (Castell, Borchert, and Zucker, 168)

Maslow�s Hierarchy of Needs provides a modest model for those seeking to attain autonomy. As seen in this model, the fifth level of Self-Actualization cannot possibly reconcile itself within the practice of religious worship. The lack of viable support for the Judeo-Christian belief structure, and all other religions based upon worship, is sufficient clause for the rejection of religious practice as a whole.

The characteristics of those within this Maslow�s fifth level are equivalent to those who have attained personal autonomy. Autonomy can be acquired only through the constant objective reflection of socially accepted truths within a person�s environment. In religious terminology, the autonomous being must remain agnostic. Yet, the refusal to accept any concept without sufficient evidence should be stoically applied in all aspects of one�s life.

Religious life in general contradicts the aims of those who aspire to reach self-actualization. In particular, the practice of religious worship works to retard the progress one may seek in gaining autonomy. For the reasons illustrated and innumerable others not represented within this text, all reasonable beings must whole-heartedly reject the worship of an unproven deity along with the continued placement of all belief systems into the realm of doubtable hypotheses.

Works Cited

Castell, Alburey, Donald Borchert, and Arthur Zucker. Introduction to Modern Philosophy: Examing the Human Condition. Seventh Edition. Ohio University. Prentice Hall Inc. New Jersey. 2001.

Hick, John. Classical and Contemporary Readings in the Philosophy of Religion. Third Edition. Claremont Graduate School. Prentice Hall Inc. New Jersey. 1990.

Lepp, Ignace. Atheism in Our Time: A Psychoanalyst�s Dissection of the Modern Varieties of Unbelief. The Macmillan Company. New York. 1971.

Lester, David, Judith Hvezda, Shannon Sullivan, and Roger Plaude. The Journal of General Psychology. Richard Stockton State College. New Jersey. 1983.

Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality. New York. Harper & Row. 1954.

Russell, Bertrand. Why I Am Not A Christian. Simon and Schuster. New York. 1957.

The Bible. Revised Standard Version.

©