Free Trade and Economic Prosperity

Rijesh Shrestha

In 1776, Adam Smith laid down the logic of limited governance, free trade, and economic development in his book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. He asserted that specialization could benefit nations as much as they could benefit firms. His reasoning were summed by the fact that cost of production differences caused relative prices to differ, which gave rise to specialization and exchange. This would lead to the trading countries to achieve greater real output and higher standard of living. In 1817, David Ricardo published Principles of Political Economy where he materialized the benefit of international trade with the theory of comparative advantage. His policy clearly implied that �liberalization of international trade will enhance the welfare of the world�s citizen� (Eun and Resnick 13). Countries will be better off if they specialize in producing commodities that they produce more efficiently and trade with one another. This will not only provide cheaper goods, but also help citizens enjoy a wide array of commodities and services not available domestically, and it will pump up the aggregate volume of commodities and services in the entire market.

Yet, contemporaries like Ch�ien Lung, the Chinese emperor, failed to comprehend Smith�s and Ricardo�s claim, and he rejected King George�s invitation for future trade between the England and China. While the Chinese adhered to Ch�ien Lung�s protectionist approach during the 1800s, the Meiji dynasty in Japan reaped benefits from their open trade policy with the West that was set up by Commodore Matthew Perry in 1854 (Folsom 3). The Japanese soon competed in textile, ships, railroad, and guns with the West. The Chinese lost wealth and land to France and England during the Opium War and they were segregated to different poles of influences by the European powers. On the other hand, the Japanese, who were quickly industrializing and advancing financially, invaded China in 1895, thrashed the Russians a decade after, and they were powerful enough to pose a threat to the West (Folsom 3). Historical evidences as such helped reinforce the theories proposed by Adam Smith and David Ricardo with greater confidence levels.

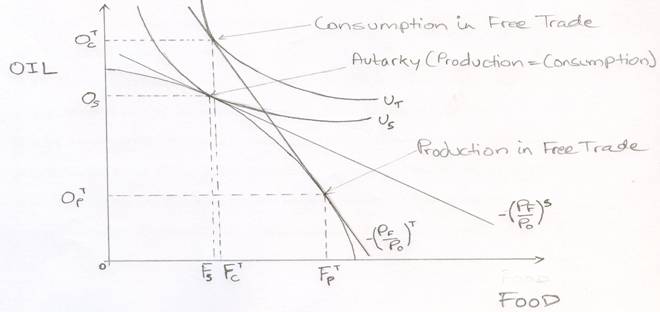

The theory of comparative advantage has helped economists to fathom the impact of international trade in the economies of the world. To illustrate the theory, the condition between the United States and the rest of the world, before and after trade, in the production of food and oil can be taken into consideration. Before trade (autarky), the States may utilize its limited resources into the production of both food and fuel. However, the aggregate consumption and utility are constrained to the volume of production of the United States. The U.S. can either choose to trade with the nations of the rest of the world, or it can always exercise it option to remain a protectionist nation and curtail trade. If the States exercise the former option as opposed to the later, it can exchange and consume different bundles of goods with its trading partners.

Addressing his Intermediate Applied Microeconomics class in Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Professor David Autor provides a sound explanation for international trade and the principle of comparative advantage in his lector notes. In the following figure presented, let the production (consumption) possibility frontier be denoted for the United States before trade for food (F) and oil (O). The price ratio (PF/PO)S is the opportunity cost of producing one more unit of food at the margin. For the sake of simplicity, let this price ratio equal to 1; hence, the slope, at the tangency with the indifference curve (US) also equals to 1. The production (consumption) of food and oil are given by FS and OS. Assuming that the U.S. market is relatively small to the world market and it cannot affect the world price; hence, the States is said to be price taker. Thus, the world price ratio (PF/PO)W is fixed and linear to the States. This price ratio is also the slope, and it is tangent to the production frontier at production units of FP and OP. Note that no country can consume beyond its budget set which is determined by the price ratios; however, once countries trade, the new budget set is not constrained by the mere domestic production possibility curve (Autor 2). If (PF/PO)S = (PF/PO)W , or if there were no market imperfections, then trade between parties would cease to exist since gains from trade would have been negated. Thus, one can perceive that the gains of trade come entirely from differences between countries and from the relative price differences. �If there were truly �a level playing field� among trading partners- as many politicians demand as a condition for trade- then there would be no point in trading� (Autor 5).

Here, IH is the new budget set since the world value of OP and FP is given by

IH = OP PWO + FP PWF

The new budget set lies above the production frontier, except for the point of tangency. Thus, the Americans can achieve a higher level of aggregate utility, which can be denoted by an outward shifting indifference curve (UT), provided they trade commodities. Since the rest of the world has a higher opportunity cost in the marginal production of food, the States are said to have a comparative advantage in the production of food. This is illustration by

(PF/PO)W > (PF/PO)S

Thus, the United States will produce more food in their vast acres of land and trade it with oil with the rest of the world. The States produce at bundle OP, FP and consumes at the bundle OC, FC that lies within the new budget set. The export volume can be given by FP � FC and the import volume can be given by OP - OC. Since the production and the consumption both lie in the budget set, there is said to be no trade imbalance. The observation that can be made is that the United States still produces within its production frontier but it can manage to consume beyond it, at a higher aggregate utility. This is the gain from trade (Autor 3).

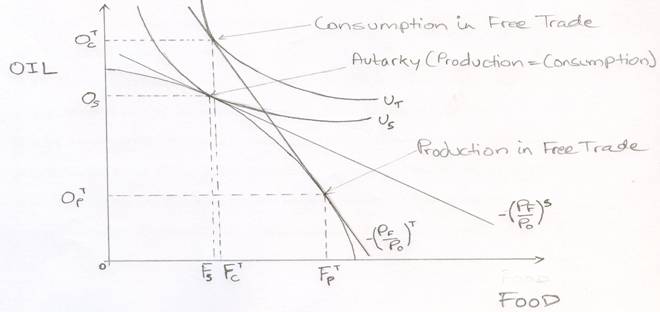

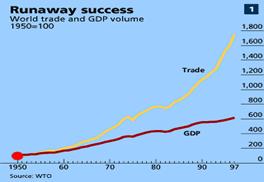

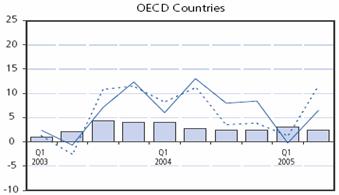

During the twentieth century, major policy changes in the realm of international trade occurred throughout the western hemisphere. After the disastrous impact of Smooth- Hawley (1930), the Trade Agreement Act of 1934 chiseled off much of the tariff rates the United States of America traditionally had. After World War II, various economies integrated in global and regional levels in the favor of trade liberalization among themselves. The Bretton Wood Conference of 1944 was held to prevent the economic nationalism with destructive �beggar-thy-neighbor� policy (Eun and Resnick 32). It held regular sessions like the Kennedy-Round (1967) in an effort to reduce barriers of trade. In 1947, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) evolved as a multilateral trade agreement with the mission of reducing various forms of trade barriers among the member countries (Eun and Resnick 13). Later during the Uruguay Round that went from 1986 to 1994, the GATT transformed and it was replaced by a permanent World Trade Organization (WTO) that implemented new structures where all the members have equal mutual rights and obligations, better known as the most-favored-nation clause (Lipsey and Chrystal 33). The success of the mission of the post-world war II trade agreements have been portrayed in the following graph. Notice that that the trade volume which has increased sixteen folds has grown faster than the GDP since the 1950 (�Time for Another Round�).

http://www.economist.com/surveys/PrinterFriendly.cfm?story_id=605130

The Twentieth Century also gave rise to various regional trade agreements between neighboring nations to facilitate commerce, political stability, and economic integration among themselves. The creation of European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, which later adapted into the European Union (EU) in 1993, stands out as a solid example of a custom union and regional integration. Trade among member nations increased by 98% in between 1958 and 1962 while the trade in the rest of the world increased by only 35%. The Trade Expansion Act of 1962, allowed the US to enter into negotiations with and penetrate the Common Market with the help of GATT which tried to erode the Common External Tariff (Krause 12). In January 1999, the EU adopted the common Euro currency to further legitimize their goals. Today, the Euro competes with U.S. dollar as a dominant currency for international trade and investment. In 1999, Mergers and acquisitions deals in Europe, which totaled $1.2 trillion, outpaced the deals made in the U.S. for the first time (Eun and Resnick 4). Several other nations around the globe have tried to form various regional trade agreements. Some conspicuous regional agreements have been the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA), the Association of Southern Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the South Asian Association for Regional Corporation (SAARC).

![]()

![]()

http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its2005_e/its05_toc_e.htm

Unlike the European nations, the American nations indulged in a free trade and eliminated the notion of common external tariff. In 1988, Canada and the United States entered an agreement for free trade between the two nations. Later in 1994, Mexico, the United States, and Canada joined hands to create the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Needless to say, NAFTA has not been immune from controversy and resistance. United States presidential candidate of the Reform Party, and billionaire American businessman, Ross Perot warned his fellow voters to listen to �the giant sucking sound� of American job heading south to Mexico should the NAFTA be endorsed. However, the �giant sucking sound� was never heard of, but instead other Latin countries who comprehended the potential gain from such a trade agreement wanted to be a part of the NAFTA, and they have proposed to create what would be known as the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). Throughout the world, NAFTA has served to be a paradigm of free trade and prosperity. ASEAN and SAARC have recently followed the wake of the Americans, and they have tried to form their own free trade agreement such as the East Asia Free Trade Area (EFTA) and South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA).

In this book The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith, a proponent of trade liberalization, had this to say about the gains of trade: ��the proposition is so very manifest, that it seems ridiculous to take any pain to prove it�� (Folsom 2). Yet, there are protectionists like Ross Perot, who waste time advocating the nuisances of free trade and waste energy and resources designing sturdy trade barriers to limit trade. From their prospective, barriers must be erected to protect their nations from cheap foreign goods, to avoid outsourcing of jobs, to protect key and infant industries, to solve enormous deficit payment problems, and to stop exploitation and environmental degradation.

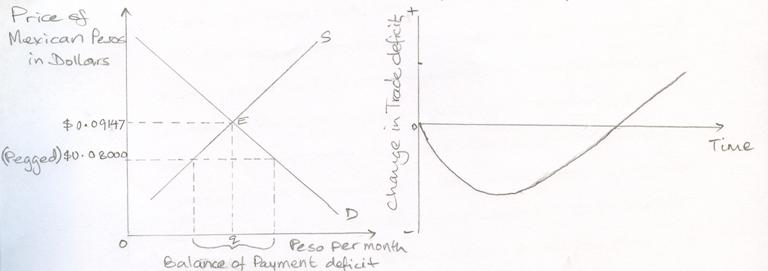

In the recent years, the later two arguments have gathered much heat and public support. A great deal of energy has been spent to highlight trade deficit and exaggerate its effect. The balance of payment is a double-entry bookkeeping national income accounting. Even though the United States has an enormous trade deficit, the balance of payment remains balanced due to the capital account, for the exception of some statistical discrepancies. In his book Capitalism and Freedom, Milton Friedman clearly mentions the condition consistent with a free market and free trade as, ��a system of free floating exchange rates determined in the market by private transaction without government intervention�if we do not adapt it, we shall inevitably fail to expand the area of free trade and shall sooner or later be induced to impose widespread direct control over trade� (Friedman 67). The balance of payment deficit, which is more threatening than the trade deficit, can be a consequence of pegging the exchange rate below the equilibrium level. Sebastian Edwards (1989) constructed a J-Curve that indicates trade deficits would be balance by the �invisible hand� as time progresses and exchange rates are allowed to flex freely to match the trade transactions across borders (Eun and Resnick 62).

Environmentalist blames trade for encouraging industrialization and industrialization for polluting the earth. However, pollution is consequence of the lack of solid property laws and the lack of legal private property. As Stated in Jo Kwang�s article Environment and Free Trade, Hoover research fellow Mikhail Bernstam concluded, �Resources use and discharges began to decline rapidly in those nations with competitive markets, even as economic growth continued. In contrast, during the same two decades of 1970�s and 1980�s, consumption and environmental disruption were rapidly increasing in the USSR and European socialist countries even though their economies slow down and eventually stagnated� (Folsom 163).

Personally, I have lived almost my entire life in a so-called �Third World� country. I have seen what it means for human beings to live their lives in the state of absolute poverty, and I have heard of fellow citizens who have perished because of starvation. In a nation that has very little to offer, multinational companies that could provide thousands of jobs and subsistence will be greeted by the poor as a boon. Westerners, who probably have never left their comfort zone, may view working at a factory line menial, repulsive, and being exploited, but for these workers their job is an opportunity for their survival and a chance to afford to send their children to school.

If consumers outweigh producers in the broad market, and if these vast numbered consumers reap the benefit of cheaper imported goods, why do they not appeal against protectionism? What drives producers to be protectionists? The answer lies in the incentives that motivate people. Even though all consumers enjoy the cheaper goods, lowered price are distributed equally to the vast numbered customers. The marginal cost to each customer is very high to allocate time and money to lobby the legislatives for a reduction of barriers. However, an increase in market share due to trade barrier mechanisms can reward the producers with a handsome profit. Their marginal benefit, as protectionist, increase with the increase of trade barrier legislations. Hence, they have more incentives to spend more time and more money lobbying for their special benefits with the legislators (Cox and Alm 4).

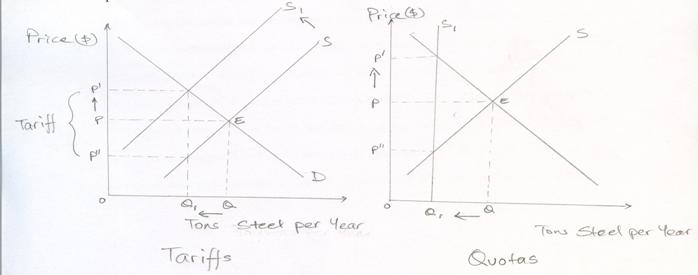

In an effort to facilitate a few special interests, legislators around the globe have designed and built sophisticated trade barriers that hurt the general interest of their people, customers at majority, who are reduced to shop for either expensive alternatives or do without them at all. Among numerous barriers, tariff, quotas, embargo, and voluntary restraints have been commonplace in various economies of the world. Furthermore, other inconspicuous forms of barriers have been devised to frustrate foreign imports such as the antidumping law, licensing, subsidies, tax breaks, public health regulations, transactions cost, local content law, cultural differences, and government purchase restrictions.

Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported commodities and services, and it was an important source of government revenues. Tariff cuts back the cheaper foreign supplies in a given market, shifting the supply curves to the left and resulting less commodities, in aggregate, in the given market. While some of the tax burden is borne by the producer, some of it is borne by the customers. Furthermore, lack of foreign substitutes causes the demand of domestic products to increase which leads to the prices of the domestic products to increase as well.

Quotas are limits assigned to foreign trade entering into domestic markets. The limitation of foreign import constricts the commodities available in the market, forcing customers to shop for higher priced domestic alternatives. Unfortunately, prices of these alternatives rises as more people depend on them. Embargos are simply boycotts of foreign goods, like the Unites States had with Cuba.

In 1962, Milton Friedman remarks in Capitalism and Freedom, �while tariffs are bad, quotas and other direct interferences are even worse�perhaps worse than either tariff or quotas are extra-legal arrangements, such as the �voluntary� agreements by Japan to restrict textile exports� (Friedman 66). In 1987, Friedman explains the effect such restraints, �The �voluntary� restraints in effect legitimizes a government-enforced cartel of Japanese auto products, enabling them to limit sales, raise prices, and pocket the differences� (Friedman 22). The ultimate consequences of trade barriers are that it limits quantity and raises price in the market for customers. In effect, it has similar consequences as a regressive taxation since poor people have to spend proportionally more out of their given income, compared to the richer people, for the same product.

As human civilizations have evolved over the centuries, commerce has also evolved. Commerce has molded the diplomatic relationship between nations and it has helped transformed us to be a part of a more cooperative civilization. Hans F. Sennholz points out in his essay Protectionism and Unemployment, �(Mercantilism during the 1930�s) guided by a spirit of nationalism it sought national self-sufficiency through restrictive tariffs, import quotas, and exchange rate restrictions. It differed from the older mercantilism in that it received strength and support from a philosophy of militant nationalism and economic welfarism� (Folsom 142). The history of world civilizations vividly portrays episodes of barbaric warfare and invasions for the purpose of capital accumulation to satisfy the desire for mass consumption. Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers Party marched eastwards in Europe to amass their precious resources to fulfill his dream of an Aryan race. The Soviet Union and the Red Army savaged their way west in a hope of building a giant nation. The Japanese Empire flourished in East Asia in an effort to gather capital to fuel their growing economy, annexing Manchuria Province, Thailand, Indonesia, Inner Mongolia, Burma, and other islands but leaving behind atrocities like the Rape of Nanking. Free trade can help eliminate such barbarism and atrocities, and it has helped us to be more civilized creatures. Human beings can now trade vast amounts of cheaper substitutes across boarders to fulfill their needs without having to invade and pillage one another.

In his book The Common Market, Lawrence B. Krause states, �economic integration will supposedly have some immediate (static) effect upon the member countries and will also cause some changes over a long period of time (dynamic effect)� (Krause 8). The Heritage Foundation indicate that research and statistical evidences, like the graph below, suggest that among the various categories of economic integration, one that advocates more trade and market freedom are the ones that have sounder economic performance.

The Static advantages that can be achieved through free trade are specialization and efficiency, labor and capital reallocation, and availability of goods and services at cheaper price. With the United State�s participation in free international trade, it is inevitable that established businesses will be closed down and people will suddenly find themselves unemployed. However, this is simply the process of the theory of comparative advantage rather than the end. �Joseph Schumpeter, more than half a century ago, termed this process as creative destruction. When competing for customers, producers adopt new technologies, improve production methods, expand markets and introduce new and better products. His famous phrase captured the essence of capitalism: continuous change � out with the old, in with the new� (Cox and Koo 3). This would help us understand the federal government�s prediction of some job increases of accountants, special education positions, hazardous material removal specialists, creative computer software engineers, automotive technicians, veterinary technicians, and farm managers. Some of these specialized positions can possibly increase from 14 to as much as 27 percent through 2014 (Kingsburg 56).

Merchandise Export / GDP at 1990 Price, in Percent

|

Country |

Before NAFTA (1973) |

After NAFTA (2001) |

|

United States |

5.0 |

7.2 |

|

Canada |

19.9 |

41.1 |

|

Mexico |

2.2 |

28.7 |

Source: International Financial Management, Eun / Resnick (page 12, exhibit 1.3)

The above table clearly indicates that all three nations gained in export after the inception of NAFTA and the liberalization of international trade throughout the world. Mexico drastically improved its export to GDP from 2.2% to a 28.7% high, and Canada increased by 21.2%. The United States also improved its export to GDP from a 5.0% to a 7.2%. While all the trade partners were better off, none of them where worse off from trade agreement. The North American Trade Agreement proved to be a voluntary contract that achieved Pareto Optimality.

The graph below explicitly depicts the pattern of unemployment of the United States before and after the period of the inception and adaptation of the NAFTA. One can see that the unemployment rate in the 1980�s was extremely high. Even before the NAFTA was introduced, from 1989 to 1992, the unemployment rate was soaring high from 5.3% to 7.5%. However, unlike Ross Perot�s vision, after the NAFTA, the unemployment rate actually dropped from 7.5% to 4% in 2000; it is one of the lowest rates in the past half of the century. The rate climbed to 6.2% again in 2003, which could be blamed for the recession of November 2001. Ross Perot�s mercantilist perspective underestimated the benefits that international trade and trade agreement had in store for the domestic and global economy.

Source: Economics of Social Issues, Sharp / Register/ Grimes (Page 303, Figure 11.2)

The dynamic consequences of free trade are the increase in competition, larger markets, growth of subsidiary and financial market, and growth of investment. Large markets result due to economies of scales that are enjoyed by larger plants producing large outputs to fulfill global demands of commodities. The graph below indicates the growth of the markets in the NAFTA nations over time.

http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/nafta-alena/menu-en.asp

Free trade helps move the economy towards perfect competition

by increasing competition among producers and customers and decreasing

monopolistic market forms. Perfect competition provides cheaper goods through

allocative efficiency, at point where marginal cost of making an

additional unit equals market price. As markets grow larger and more

specialized, demand for advertising agencies, management consultancies,

repairing industries, and financial institutions also grow. As efficiency and

productivity increases, the rate of economic growth of the market and industries

rises. Furthermore, investing overseas in different growing economies with

varying rates of return will reduce risk of the diversified portfolios that

investors can now hold. This could enhance investment opportunities and boost

the investor�s wealth.

I was delighted to read about the recent agreement made by the South Asian Associations for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) which made headlines across the region. �The SAARC announced the formal enforcement of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement after all the members, including Nepal, ratified the agreement on national levels� (www.nepalnews.com). The mission is to reduce tariff by 30 percent in Least Developed Countries and 20 percent in Developing Countries so as to bring tariff down between 0 and 5 percent by 2016 and 2009 in the respective countries. Even though the Himalayan Kingdom has multitudinous task to resolve, it has executed one of the most crucial strategy towards potential economic prosperity. As the nation reforms, it must take full advantages of the opportunities offered by its neighboring countries, especially the two emerging economic powerhouse of this century, China and India. As Adam Smith suggested, ��It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy� If a country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage�� (Grossman).

Work Cited

Autor, David. �Lecture: International Trade and the Principle of Comparative Advaantage.� Lecture. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Boston. Fall 2004.

Cox, W. Michael, and Jahyeong Koo. �Miracle of Malaise: What�s Next For Japan?� Economic Letter. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Dallas, TX. Vol. 1, No. 1, January 2006.

Cox, W. Michael, and Richard Alm. �The Fruits of Free Trade.� The Insider No. 309, August 2003: 4.

Eun, Cheol S., and Bruce G. Resnick. International Financial Management. Third ed. New Delhi: Tara McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, 2004.

Forlsom, Jr., Burton W., ed. The Industrial Revolution and Free Trade. Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: the Foundation of Economic Education,1996.

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

---. �Outdoing Smoot-Hawley.� The Wall Street Journal 20 April 1987: 22

Grossman, Andrew, ed. �Editor�s Note.� The Insider. Washington D.C., August 2003.

Kingsburg, Alex. �Where the Hiring Is the Hottest.� U.S. News and World Report. 20 March, 2006.

Krause, Lawrence B., The Common Market. Englewood Cliff, NJ. Prentice-Hall, Inc.,1964.

Lipsey, Richard G., and K. Alex Chrystal. Economics. Tenth ed. New Delhi. Oxford University Press, 2004.

�SAFTA Agreement Comes Into Force.� NepalNews. 24 March 2006. <http://www.nepalnews.com/archive/2006/mar/mar24/news12.php>.

�Time for Another Round.� The Economist. 1 October 1998. 27 March 2006 <http://www.economist.com/surveys/PrinterFriendly.cfm?story_id=605130>.

©